Beej's Quick Guide to GDB

Release 2 (2009 Jun 14) This is a very quick-and-dirty guide meant to get you started with the GNU Debugger, gdb, from the command line in a terminal. Often times gdb is run via an IDE, but many people out there shun IDEs for a variety of reasons, and this tutorial is for you!

Again, this is only a getting-started guide. There's much much MUCH more to learn about what the debugger does than is written in these few short paragraphs. Check out your "man" pages or the online resources listed below for more info.

This tutorial is meant to be read in order, up to, but not including, the "Misc" section.

Contents

- Compiling to use a debugger

- More Information

- License

- Starting gdb and getting to main()

- Breakpoints

- Stepping Around

- Examining Variables

- Misc Stuff

- Stack Manipulation

- Additional Stepping Methods

- Jumping to an Arbitrary Section of Code

- Changing Variables and Values at Runtime

- Hardware Watchpoints

- Attach to a Running Process

- Using Coredumps for Postmortem Analysis

- Window Functions

- Display Registers and Assembly

- Writing a Front-End

- Quick Reference Cheat Sheet

Compiling

You have to tell your compiler to compile your code with symbolic debugging information included. Here's how to do it with gcc, with the -g switch:

$ gcc -g hello.c -o hello

$ g++ -g hello.cpp -o hello

Once you've done that, you should be able to view program listings in the debugger.

More Information

Check out the Official GDB Documentation for more information than you can shake a stick at!

Also, a good GNU GDB front-end is DDD, the DataDisplayDebugger.

License

Creative Commons License Beej's Quick Guide to GDB by Brian "Beej Jorgensen" Hall is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Starting The Debugger

First things first: you can enter help at any gdb prompt and get more information. Also, you can enter quit to quit the debugger. Finally, just hitting RETURN will repeat the last command entered. Now let's fire it up!

There are several ways to start the debugger (e.g. if you were an IDE you might start it with a particular mode that's not so human-friendly) but I'll mention two of them here: vanilla console mode and curses GUI mode. The GUI is better, but let's quickly cover the simple one, and launch a program called hello in the debugger:

$ gdb hello

GNU gdb 6.8

Copyright (C) 2008 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

License GPLv3+: GNU GPL version 3 or later <http://gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html>

This is free software: you are free to change and redistribute it.

There is NO WARRANTY, to the extent permitted by law. Type "show copying"

and "show warranty" for details.

This GDB was configured as "i486-slackware-linux"...

(gdb) run

Starting program: /home/beej/hello

Hello, world!

Program exited normally.

(gdb)

The last line is the gdb prompt, waiting for you to tell it what to do. Type r or run to run the program. (gdb allows you to abbreviate commands until they become ambiguous.)

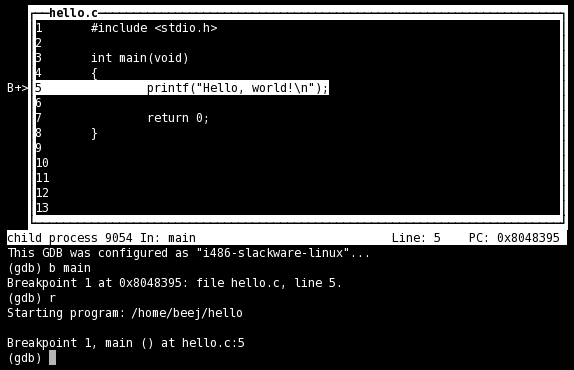

To start in neato and highly-recommended GUI mode, start the debugger with gdb -tui. (For many of the examples, below, I show the output of gdb's dumb terminal mode, but in real life I use TUI mode exclusively.)

And here is a screenshot of what you'll see, approximately:

All the normal gdb commands will work in GUI mode, and additionally the arrow keys and pgup/pgdown keys will scroll the source window (when it has focus, which it does by default). Also, you can change which file or function is displayed in the source window by giving the command list with a location as an argument, for example, "list hello.c:5 to bring up the file hello.c on line 5. (See "Breakpoints", below, for sample locations—the same locations that work with breakpoints will work with the list command.) As a side note, list also works in dumb terminal mode.

Now, notice that we passed the name of the executable on the command line. Another option you have is to just start gdb with nothing else on the command line, then give it the command file hello, and that will cause the executable "hello" to be loaded up.

Command line arguments! What if you have to get something into argv in your program? Pass them as arguments to the run command when you start execution:

$ gdb hello

GNU gdb 6.8

Copyright (C) 2008 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

License GPLv3+: GNU GPL version 3 or later <http://gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html>

This is free software: you are free to change and redistribute it.

There is NO WARRANTY, to the extent permitted by law. Type "show copying"

and "show warranty" for details.

This GDB was configured as "i486-slackware-linux"...

(gdb) run arg1 arg2

Starting program: /home/beej/hello arg1 arg2

Hello, world!

Program exited normally.

(gdb)

Notice where it says "Starting Program", above, it shows the arguments "arg1" and "arg2" being passed to "hello".

Breakpoints

Just starting the debugger to run the program straight through isn't very useful—we need to stop execution and get into stepping mode.

First, before you issue the run command, you need to set a breakpoint someplace you'd like to stop. You use the break or b command, and specify a location, which can be a function name, a line number, or a source file and line number. These are examples of locations, which are used by various other commands as well as break:

break main Break at the beginning of the main() function

break 5 Break at line 5 of the current file

break hello.c:5 Break at line 5 of hello.c

So for this test, let's set a breakpoint at main(), and start the program:

$ gdb hello

GNU gdb 6.8

Copyright (C) 2008 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

License GPLv3+: GNU GPL version 3 or later <http://gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html>

This is free software: you are free to change and redistribute it.

There is NO WARRANTY, to the extent permitted by law. Type "show copying"

and "show warranty" for details.

This GDB was configured as "i486-slackware-linux"...

(gdb) b main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x8048395: file hello.c, line 5.

(gdb) r

Starting program: /home/beej/hello

Breakpoint 1, main () at hello.c:5

5 printf("Hello, world!\n");

(gdb)

As you see, we've arrived at main() and execution has stopped at the breakpoint we set there. If you're running in dumb terminal mode, gdb will print the line it will execute next. If you're running in cool GUI mode, the line it will execute next will be highlighted in the source window.

To list the current breakpoints, use the info command, like so: "info breakpoints" (or the shorter "i b"):

(gdb) b main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x8048395: file hello.c, line 5.

(gdb) i b

Num Type Disp Enb Address What

1 breakpoint keep y 0x08048395 in main at hello.c:5

To clear a breakpoint, use the clear command with the breakpoint location. You can also clear a breakpoint by number with the delete command.

Additionally, you can enable or disable breakpoints, though these two commands take a breakpoint number as an argument, not a location! The enabled/disabled status of a breakpoint is visible under the "Enb" column in the breakpoint listing.

(gdb) i b

Num Type Disp Enb Address What

1 breakpoint keep y 0x08048395 in main at hello.c:5

(gdb) disable 1

(gdb) i b

Num Type Disp Enb Address What

1 breakpoint keep n 0x08048395 in main at hello.c:5

(gdb) clear main

Deleted breakpoint 1

(gdb) i b

No breakpoints or watchpoints.

Stepping Around

Once execution stops at a breakpoint, you can tell the debugger to do a few things. Let's start with the next command (or n). This command moves you to the next statement in the current function (or returns to the function's caller if you've stepped off the end of the function.) Here's a sample run; remember that gdb is printing the line it will execute next just before the "(gdb)" prompt. Also notice that when we run next on the printf() line, we see the output appear.

(gdb) b main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x8048395: file hello.c, line 5.

(gdb) r

Starting program: /home/beej/hello

Breakpoint 1, main () at hello.c:5

5 printf("Hello, world!\n");

(gdb) next

Hello, world!

7 return 0;

(gdb) next

8 }

(gdb) next

0xb7d6c6a5 in __libc_start_main () from /lib/libc.so.6

(gdb) next

Single stepping until exit from function __libc_start_main,

which has no line number information.

Program exited normally.

(gdb)

(That weird stuff at the end about __libc_start_main() shows you that there was another function that called your main() function! It wasn't compiled with debugging information so we can't see the source, but we can still step through it—which we do—and the program exits normally.)

Now, notice that next steps over function calls. This doesn't mean that function doesn't get called; it means that next will execute the function until it's done, and then return you to the next line in your current function.

What if you have a function you want to step into from your current function, and trace through that function line-by-line? Use the step (or s) command to do this. It works just like next, except it steps into functions.

Let's say you're tired of single stepping, and just want the program to run again. Use the continue (or c) command to continue execution.

What if the program is running but you forgot to set breakpoints? You can hit CTRL-C and that'll stop the program wherever it happens to be and return you to a "(gdb)" prompt. At that point, you could set up a proper breakpoint somewhere and continue to that breakpoint.

One final shortcut is that just hitting RETURN will repeat the last command entered; this will save you typing next over and over again.

Examining Variables

If you have some variables you wish to inspect over the course of the run, you can display them, but only if the variable is currently in scope. Each time you step the code, the value of the variable will be displayed (if it's in scope).

(The following output is missing source code output between lines for clarity—it's what you'd see in GUI mode. Imagine you're seeing the highlight bar bouncing around the source code while you're running this:)

(gdb) b main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x8048365: file hello.c, line 5.

(gdb) r

Starting program: /home/beej/hello

Breakpoint 1, main () at hello.c:5

(gdb) disp i

1: i = -1207447872

(gdb) next

1: i = 1

(gdb) next

1: i = 1

(gdb) next

1: i = 2

(gdb) next

1: i = 2

(gdb) next

1: i = 4

(gdb) next

1: i = 4

(gdb) next

1: i = 4

(gdb)

The number to the left of "i", above, is the display number of the variable. Use this number to undisplay the variable. If you forget the display numbers, you can type info display to get them:

(gdb) b main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x8048365: file hello.c, line 5.

(gdb) r

Starting program: /home/beej/hello

Breakpoint 1, main () at hello.c:5

(gdb) display i

1: i = -1207447872

(gdb) info display

Auto-display expressions now in effect:

Num Enb Expression

1: y i

(gdb) undisplay 1

(gdb)

If you just want to one-off know the value of a variable, you can print it. Here we see the value of "i" is 40:

(gdb) print i

$1 = 40

(gdb)

(The "$" with the number after it means something, but it's not important for beginners.)

There's also a handy printf command that you can use to better format your output if you want to:

(gdb) printf "%d\n", i

40

(gdb) printf "%08X\n", i

00000028

(gdb)

Misc Stuff

This is stuff that doesn't really fit in the earlier sections, but it fun enough to list somewhere.

Stack Manipulation

The command backtrace (or bt) will show you the current function call stack, with the current function at the top, and the callers in order beneath it:

(gdb) backtrace

#0 subsubfunction () at hello.c:5

#1 0x080483a7 in subfunction () at hello.c:10

#2 0x080483cf in main () at hello.c:16

(gdb)

Type help stack for more info on what you can do with this.

Additional Stepping Methods To exit the current function and return to the calling function, use the finish command.

To step for a single assembly instruction, use the stepi command.

To continue to a specific location, use the advance command, specifying a location like those shown in the "Breakpoints" section, above. Here's an example which advances from the current location until the function subsubfunction() is called:

Breakpoint 1, main () at hello.c:15

15 printf("Hello, world!\n");

(gdb) advance subsubfunction

Hello, world!

subsubfunction () at hello.c:5

5 printf("Deepest!\n");

(gdb)

advance is just shorthand for "continue to this temporary breakpoint."

Jumping to an Arbitrary Section of Code

The jump command works exactly like continue, except it takes a location to jump to as an argument. (See the the "Breakpoints" section, above, for more information on locations.)

If you need to stop at the jump destination, set a breakpoint there first.

Changing Variables and Values at Runtime

You can use the set variable command with an expression to evaluate, and this allows you to change the value of a variable during the run. You can also shorthand this by just using set with a parenthesized expression after it:

Breakpoint 1, main () at hello.c:15

15 int i = 10;

(gdb) print i

$1 = -1208234304

(gdb) set (i = 20)

(gdb) print i

$2 = 20

(gdb) set variable i = 40

(gdb) print i

$3 = 40

(gdb)

This, along with the jump command, can help you repeat sections of code without restarting the program.

Hardware Watchpoints Hardware watchpoints are special breakpoints that will trigger whenever an expression changes. Often you just want to know when a variable changes (is written to), and for that you can use the watch command:

Breakpoint 1, main () at hello.c:5

5 int i = 1;

(gdb) watch i

Hardware watchpoint 2: i

(gdb) continue

Continuing.

Hardware watchpoint 2: i

Old value = -1208361280

New value = 2

main () at hello.c:7

7 while (i < 100) {

(gdb) continue

Continuing.

Hardware watchpoint 2: i

Old value = 2

New value = 3

main () at hello.c:7

7 while (i < 100) {

(gdb)

Note that watch takes an expression as an argument, so you can put a variable name in there, or something more complex like *(p+5) or a[15]. I've even tried it with conditional expressions like i > 10, but have had mixed results.

You can get a list of watch points with info break or info watch, and you can delete them by number with the delete command.

Finally, you can use rwatch to detect when a variable is read, and you can use awatch to detect when a variable is either read or written.

Attach to a Running Process

If your program is already going and you want to stop it and debug, first you'll need the process ID (PID), which will be a number. (Get it from Unix's ps command.) Then you'll use the attach command with the PID to attach to (and break) the running program.

For this, you can just start gdb with no arguments.

In the following complete run, you'll notice a few things. First I attach to the running process, and it tells me it's in some function deep down called __nanosleep_nocancel(), which isn't too surprising since I called sleep() in my code. Indeed, asking for a backtrace shows exactly this call stack. So I say finish a couple times to get back up to main().

$ gdb

GNU gdb 6.8

Copyright (C) 2008 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

License GPLv3+: GNU GPL version 3 or later <http://gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html>

This is free software: you are free to change and redistribute it.

There is NO WARRANTY, to the extent permitted by law. Type "show copying"

and "show warranty" for details.

This GDB was configured as "i486-slackware-linux".

(gdb) attach 3490

Attaching to process 3490

Reading symbols from /home/beej/hello...done.

Reading symbols from /lib/libsafe.so.2...done.

Loaded symbols for /lib/libsafe.so.2

Reading symbols from /lib/libc.so.6...done.

Loaded symbols for /lib/libc.so.6

Reading symbols from /lib/libdl.so.2...done.

Loaded symbols for /lib/libdl.so.2

Reading symbols from /lib/ld-linux.so.2...done.

Loaded symbols for /lib/ld-linux.so.2

0xb7eab21b in __nanosleep_nocancel () from /lib/libc.so.6

(gdb) backtrace

#0 0xb7eab21b in __nanosleep_nocancel () from /lib/libc.so.6

#1 0xb7eab05f in sleep () from /lib/libc.so.6

#2 0x080483ab in main () at hello.c:10

(gdb) finish

Run till exit from #0 0xb7eab21b in __nanosleep_nocancel ()

from /lib/libc.so.6

0xb7eab05f in sleep () from /lib/libc.so.6

(gdb) finish

Run till exit from #0 0xb7eab05f in sleep () from /lib/libc.so.6

0x080483ab in main () at hello.c:10

10 sleep(1);

(gdb) list

5 {

6 int i = 1;

7

8 while (i < 60) {

9 i++;

10 sleep(1);

11 }

12

13 return 0;

14 }

(gdb) print i

$1 = 19

(gdb) quit

The program is running. Quit anyway (and detach it)? (y or n) y

Detaching from program: /home/beej/hello, process 3490

Notice that when I get back to main(), I print the value of i and it's 19—because in this case the program has been running for 19 seconds, and i gets incremented once per second.

Once we've quit the debugger and detached from the program, the program returns to running normally.

Mix this with set variable, above, and you've got some power!

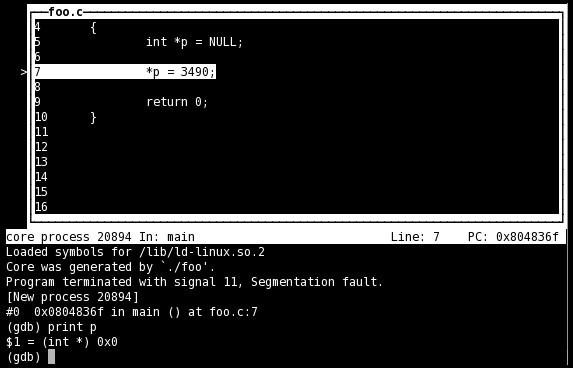

Using Coredumps for Postmortem Analysis

Let's say you build and run a program, and it dumps core on you for some reason or another:

$ cc -g -o foo foo.c

$ ./foo

Segmentation fault (core dumped)

This means that a core file (with a memory snapshot from the time of the crash) has been created with the name "core". If you're not getting a core file (that is, it only says "Segmentation fault" and no core file is created), you might have your ulimit set too low; try typing ulimit -c unlimited at your shell prompt.

You can fire up gdb with the -c option to specify a core file:

$ gdb -tui -c core foo

And, if in TUI mode, you'll be greeted with a screen of information, telling you why the program exited ("signal 11, Segmentation fault"), and the highlight will be on the offending line. (In dumb terminal mode, the offending line is printed out.)

In this example, I print the variable that's causing the problem. Indeed it is NULL:

Even if you don't have all the source code, it's often useful to get a backtrace from the point the program crashed.

Window Functions

In TUI mode, you can get a list of existing windows with the info win command. You can then change which window has focus with the focus (or fs) command. focus takes either a window name, or "prev" or "next" as an argument. Valid window names are "SRC" (source window), "CMD" (command window), "REGS" (registers window), and "ASM" (assembly window). See the next section for how to use these other windows.

Note that when the SRC window has focus, the arrow keys will move the source code, but when the CMD window has focus, the arrow keys will select the previous and next commands in the command history. (For the record, the commands to move the SRC window single lines and single pages are +, -, <, and >.)

(gdb) info win

SRC (36 lines) <has focus>

CMD (18 lines)

(gdb) fs next

Focus set to CMD window.

(gdb) info win

SRC (36 lines)

CMD (18 lines) <has focus>

(gdb) fs SRC

Focus set to SRC window.

(gdb)

(Window names are case in-sensitive.)

The winheight (or wh) command sets the height of a particular window, but I've had bad luck with this working well.

Display Registers and Assembly

In TUI mode, the layout command controls which windows you see. Additionally, the tui reg allows control of the register window, and will open it if it's not already open.

The commands are:

layout src Standard layout—source on top, command window on the bottom

layout asm Just like the "src" layout, except it's an assembly window on top

layout split Three windows: source on top, assembly in the middle, and command at the bottom

layout reg Opens the register window on top of either source or assembly, whichever was opened last

tui reg general Show the general registers

tui reg float Show the floating point registers

tui reg system Show the "system" registers

tui reg next Show the next page of registers—this is important because there might be

pages of registers that aren't in the "general", "float", or "system" sets

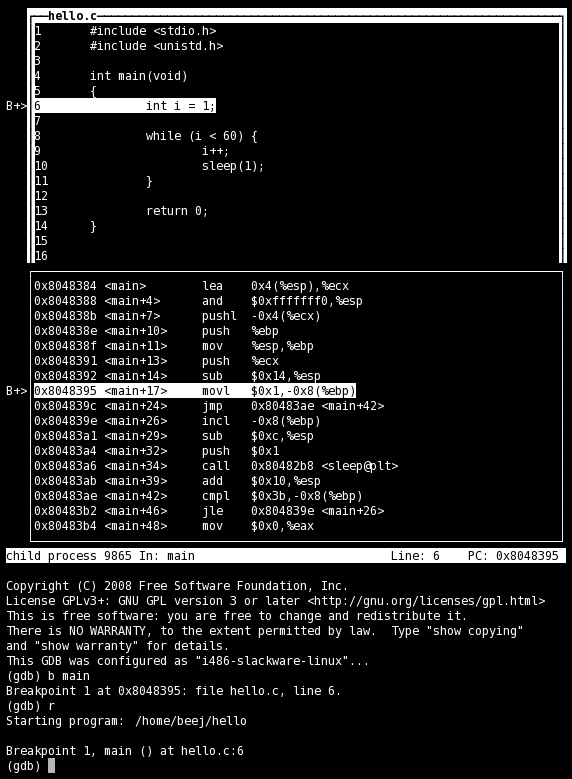

Here's a nifty screenshot to whet your appetite, showing source and assembly in "split" mode:

Assembly code comes in two flavors on Intel machines: Intel and AT&T. You can set which one appears in the disassembly window with set disassembly-flavor. Valid values are "intel" and "att". If you already have the assembly window open, you'll have to close it and reopen it (layout src followed by layout split, for example.)

To display registers in dumb terminal mode, type info registers for the integer registers, or info all-registers for everything.

Writing a Front-End

You're thinking, "Wow, this is pretty cool, but I could write a killer front-end for this thing that worked so much better! How do I do it?"

GDB supports what it calls the "machine interface interpreter", or GDB/MI. The interpreter is selected on the gdb command line with the --interpreter switch.

Basically you'll launch gdb and read commands and results to and from it (probably using pipes). Pretty straightforward.

See the GDB documentation for all the details.

Quick Reference

Command parameters are in italics. Optional parameters are in square brackets. All commands can be abbreviated until they become ambiguous.

This list is very very incomplete, and only shows things talked about in this tutorial!

Help Commands

help command Get help on a certain command

apropos keyword Search help for a particular keyword

Starting and Quitting

gdb [-tui] [-c core] [exename] (Unix Command) Start gdb on an executable or standalone; specify "-tui" to start the TUI GUI; specify "-c" with a corefile name to see where a crash occurred

run [arg1] [arg2] [...] Run the currently loaded program with the given command line arguments

quit Exit the debugger

file exename Load an executable file by name

Breakpoints and Watchpoints

break location Set a breakpoint at a location, line number, or file (e.g. "main", "5", or "hello.c:23")

watch expression Break when a variable is written to

rwatch expression Break when a variable is read from

awatch expression Break when a variable is written to or read from

info break Display breakpoint and watchpoint information and numbers

info watch Same as info break

clear location Clear a breakpoint from a location

delete num Delete a breakpoint or watchpoint by number

Stepping and Running

next Run to the next line of this function

step Step into the function on this line, if possible

stepi Step a single assembly instruction

continue Keep running from here

CTRL-C Stop running, wherever you are

finish Run until the end of the current function

advance location Advance to a location, line number, or file (e.g. "somefunction", "5", or "hello.c:23")

jump location Just like continue, except jump to a particular location first.

Examining and Modifying Variables

display expression Display the value of a variable or expression every step of the program—the expression must make sense in the current scope

info display Show a list of expressions currently being displayed and their numbers

undisplay num Stop showing an expression identified by its number (see info display)

print expression Print the value of a variable or expression

printf formatstr expressionlist Do some formatted output with printf() e.g. printf "i = %d, p = %s\n", i, p

set variable expression Set a variable to value, e.g. set variable x=20

set (expression) Works like set variable

Window Commands

info win Shows current window info

focus winname Set focus to a particular window bby name ("SRC", "CMD", "ASM", or "REG") or by position ("next" or "prev")

fs Alias for focus

layout type Set the window layout ("src", "asm", "split", or "reg")

tui reg type Set the register window layout ("general", "float", "system", or "next")

winheight val Set the window height (either an absolute value, or a relative value prefaced with "+" or "-")

wh Alias for winheight

set disassembly-flavor flavor Set the look-and-feel of the disassembly. On Intel machines, valid flavors are intel and att

Misc Commands

RETURN Hit RETURN to repeat the last command

backtrace Show the current stack

bt Alias for backtrace

attach pid Attach to an already-running process by its PID

info registers Dump integer registers to screen

info all-registers Dump all registers to screen